Wartime poultry-keeping.

Whilst growing up I was fascinated with the stories my father and grandfather would tell me about their memories of poultry when they were children. This is one that always stuck in my mind and made me appreciate how lucky we are in our current generation.

During the 1939-1945 World War, poultry in the British Isles contributed greatly to the countries economy. They were a perfect example of how to almost eliminate wastage. Converting every possible source of supply into high protein food to help maintain a healthy diet for the nation.

Developments

At this period in time the large multi-million pounds companies had not arrived into this country. Most of the poultry were kept by general farmers in varying amounts of birds. There were also the specialised Poultry Farmers. However, the war created a new group of poultry keepers, encouraged by the government to assist with feeding the population.

My father believed that during the course of the war some of the rules connected with these small poultry keepers were altered. Basically these ‘Domestic Poultry Keepers’ were allowed to keep up to 25 head of laying females without being registered. The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Foods were the government body overseeing this condition.

They were expected, by one method or another, to provide themselves with the necessary food for the birds requirements. Very often with help from their neighbours who in turn received some newly laid eggs.

Anyone else with over 25 laying birds had to be fully registered and recorded with the Ministry. In return received an allocation of food permits that enabled them to buy pellets, mash and whole corn from their local merchants.

Registered breeders

If you were a specialist breeder of long established pure bred birds you were also registered. This allowed you to receive a fixed amount of these food permits. In my families our own case my grandfather received both types of food allocations. Firstly for our battery laying hens and secondly to maintain our true bred show birds.

This Government legislation proved to be very clever foresight. After the war, a gentleman called Cyril Thornborrow created the first Hybrid laying birds. I understand that he used eleven different pure breeds to achieve all the characteristics required. This included good food conversion ratio, quick maturity, plenty of vigour combined with the correct egg texture and colour. The last feature I believe came from Silver Laced Wyandottes.

Commercial production

At this period ‘Battery Cages’ were now being perfected in a fully metal construction, whereas previously they had wooden framework. This made them stronger and instead of each cage having to be individually cleaned out by hand. A scraper had been perfected to be pulled through the whole length of the cage dropping area. Thus cleaning out a whole length of cages in one operation.

These cages were designed for a single bird. Each one had a food hopper that was topped up daily and a constant supply of clean water. The birds thrived. There was no bullying of the smaller and less dominant pullets and they laid magnificently in warmth and comfort.

Economical Feeding

The next part demonstrates how in times of hardship and suffering, success can be achieved by dedicated cooperation. The amount of food allocated by these food coupons was not sufficient to feed your stock. Therefore you had to look for every possible addition.

Small potatoes (Chats) were one source and most of the poultry farms had some type of cooking arrangements for them. Our family also collected from the local fishmongers all their offal and various types of vegetable waste. All of this was added to the cooking boiler, which in our case held two hundredweight, (around 100 kilos.)

Any waste from the confectioners was usually quickly collected by the domestic poultry keepers, as were any leftovers from the hotels. There was very little dining out during this period, however, the chip shops could usually be relied upon for a bit of waste.

Tottenham Puddings

Collecting waste on a national scale was well organised and it originally commenced in London. Families were encouraged to save all their potato peelings, vegetable waste and any other surplus food. These were all collected by the local authorities and delivered to a factory where they were mixed with molasses and boiled. They were then moulded into large slabs weighing well over 50 kilogrammes, these were then called ‘Tottenham Puddings’.

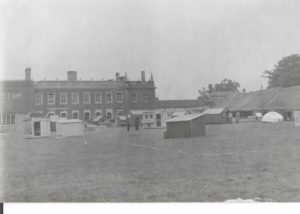

They were not on ration; it was simply a case of trying to locate some surplus ones. The idea spread around the country with all the military camps supplying large quantities of good quality waste, especially the American bases. It always amazed my grandfather how many knives, spoons, potato peelers etc. that were found in the puddings.

Smallholders

Most farms of any size had their own electric food mixers in which you put in the puddings. You then added anything you could locate to make an appetizing feed for your stock. Grass meal from America was often available, which came from lucerne grass. This was good for keeping a deep colour to the egg yolks. Bran was sometimes on the market, as was the odd bag of flaked maize.

If you were lucky, one of the machines in the biscuit factory went wrong and these came on the market. Limestone flour added weight to your mixture and was good at helping maintain strong eggshells. Cod Liver Oil was added for extra vitamins. If many of these products failed to arrive we would tip a couple of buckets of clean fine sawdust in the mixer. The nutritional value was low but at least it helped to give the birds a full crop for their nights rest.

Wet mash

It was usual to add some hot water to the mixer and the result was usually known as ‘Wet Mash’. In parts of the North it also assumed the name of ‘Soft Jock’.

Controls for the retail sale of eggs were very strict if you kept over 25 birds. You were therefore a registered producer and all your eggs had to go to the local packing station.

They were collected weekly by their own transport and were graded into sizes etc. and you were paid accordingly. The only exception to this rule was any cracked or severely mis-shaped eggs. These were cracked into containers going to your local confectioners as liquid egg and used for cake making.

Incubation and clear eggs

The next piece of nostalgic information may surprise some people. If you ran your own incubator, which we did, using a Hamer 1000 egg cabinet machine. You were instructed to test the eggs as soon as possible with 5-7 days being recommended.

All the clear eggs were then removed and individually broken into a saucer to check their contents for faults. If they were good they were put into large glass containers, usually the old fashioned sweet jars. These were then delivered to the local bakehouse for cake and custard making.

Transportation

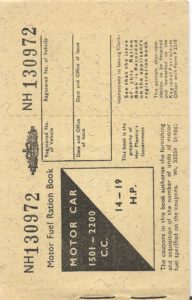

All the vehicles used to collect poultry food and waste products and also deliver to the confectioners etc. ran on petrol. This was under very strict rationing.

To obtain your allowance, a detailed plan of your route and mileage had to be submitted. Hopefully you received a sufficient amount of ‘Petrol Coupons’ to complete your journey.

This was rarely the case and you were then attempting to gain a few extra miles. One way was by adding paraffin or white spirit to your tank. This had its drawbacks where you hoped you could get the engine started on a cold morning. The petrol was called ‘Pool Petrol’ and calculated to be about 70 octane, compared to the present 98 octane.

Ration books

The younger generation of readers will probably be surprised that eating chicken was considered to be a luxury. The mass production of cheap chicken now on sale in the supermarkets had not yet commenced. In fact neither had the supermarkets!

Virtually all meat products were sold at the local butchers. Towards the end of the war the first small chickens were being reared. These to be sold purely for their carcass value.

Petit Pousins

It was normal practice that chicks hatched as future laying pullets were sexed immediately. The cockerels were killed as soon as they came out of the incubator. However, a few farms decided to experiment with rearing some of the more heavy breed type of crossed cockerels. These were reared up to an age where they had enough meat on them to make a meal. This was just before they started to develop into the ‘boney’ growing stage. These birds took their French name and were called ‘Petit Pousins’. The main advantage being they were making use of a waste product.

They were actually the beginning of today’s supermarket chickens. The modern birds have been scientifically bred to carry large quantities of meat on a fine bone body frame.

No waste

During the war there was no such thing as waste. A perfect example being after the hens had finished their economically viable laying period. Which was far longer than todays estimations, however these old hens were keenly sought after as boiling fowl. When cooked correctly they are a very under estimated meal. Also the water in which they were boiled made some excellent soup or broth.

During this time there were no controls over the retailing of poultry meat. Pigs were slightly different in that everyone with the space was encouraged to keep a pig in their garden. You were allowed a licence to kill two per year with no limit as to their size. Cattle were under strict control and only to be slaughtered at approved premises then directly into the food chain.

Protein provider

I stated earlier how Poultry had made a wonderful contribution to the economy. A vital point in this statement was their ability to supply protein via their meat. They also had their unique ability to provide a wonderful product in their eggs. They can be cooked or processed in probably twenty different ways and are full of easily available protein.

Poultry in this country successfully contributed these commodities throughout the war. This was without any vaccination or large quantities of medicines and there were no additives to the chick meal. If you got an attack of Coccidiosis, Sulphamezathine cured it providing you caught it soon enough. Virtually no other drugs were used. It was simply down to good management and well ventilated housing to prevent disease.

Unfortunately, toward the end of the war a couple of new disease appeared. Fowl Pest and Newcastle disease were soon to become a regular occurrence. They tended to strike as soon as the damp November months arrived.

Popularity

I will finish this blog on a brighter note. Sufficient true bred large fowl and Bantams had been preserved during the war. This allowed the servicemen returning from the war to re-establish their interest in showing poultry. Within a few years the fancy was to reach new heights of success. Enthusiasm not seen since the boom years of the mid 1920s. This increase in popularity has continued almost unbroken right up to present times.

All photos taken by Mr Arthur Rice and copyright of the Kay family.